bhutan

HISTORY OF BHUTAN

The historical origins of Bhutan are obscure. It is reported that some four to five centuries ago an influential lama from Tibet, Sheptoon La-Pha, became the king of Bhutan and acquired the title of dharma raja. Bhutan probably became a distinct political entity about this period. La-Pha was succeeded by Doopgein Sheptoon, who consolidated Bhutan’s administrative organization through the appointment of regional penlops (governors of territories) and jungpens (governors of forts). Doopgein Sheptoon exercised both temporal and spiritual authority, but his successor confined himself to only the spiritual role and appointed a minister to exercise the temporal power. The minister became the temporal ruler and acquired the title of deb raja. This institution of two supreme authorities-a dharma raja for spiritual affairs and a deb raja for temporal matters-existed until the death of the last dharma raja in the early 20th century. Succession to the spiritual office of dharma raja was dependent on what was considered a verifiable reincarnation of the deceased dharma raja, and this person was often discovered among the children of the ruling families. When the last dharma raja died in the 1930s, no reincarnation was found, and the practice and the office ceased to exist.

For much of the 19th century Bhutan was plagued by a series of civil wars as the governors of the various territories contended for power and influence. The office of the deb raja, in theory filled by election by a council composed of penlops and jungpens, was in practice held by the strongest of the governors, usually either the penlop of Paro or the penlop of Tongsa. Similarly, the penlops, who were to be appointed by the deb raja, in practice fought their way into office. Throughout most of Bhutanese history a continuous series of skirmishes and intrigues took place throughout the land as superseded jungpens and penlops awaited an opportunity to return to power.

In 1907, after the dharma raja had died and the deb raja had withdrawn into a life of contemplation, the then-strongest penlop, Ugyen Wangchuk of Tongsa, was “elected” by a council of lamas, abbots, councillors, and laymen to be the hereditary king (druk gyalpo) of Bhutan. The lamas continued to have strong spiritual influence.

CONSTITUTION & MONARCHY

Bhutan is a democratic constitutional monarchy, established by its first constitution in 2008. The King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, is the head of state and a symbol of unity, while a Prime Minister heads the executive power through the council of ministers. The Constitution upholds the monarchy and establishes a multi-party system with a bicameral Parliament, though the King retains a sacrosanct, non-answerable status and is mandated to protect the Constitution.

MONARCHY IN BHUTAN

HEAD OF STATE:

The King of Bhutan, also called the Druk Gyalpo, serves as the head of state and symbol of the nation's unity.

HEAD OF GOVERNMENT:

The Prime Minister is the head of government, leading the Lhengye Zhungtshog (council of ministers).

ROYAL FAMILY:

The King is not answerable in a court of law for his actions, but he is obligated to uphold the Constitution for the people's welfare. The royal family's rights and privileges are outlined in the Constitution.

THE CONSTITUTION

Democratic Foundation:

The Constitution, adopted in 2008, established a democratic constitutional monarchy where the sovereign power resides with the people.

Legislative Power:

Power is vested in the Parliament, which consists of two houses: the National Council and the National Assembly.

Transition:

The monarchy transitioned from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional one through a process initiated by the fourth King, culminating in the 2008 Constitution and the country's first elections.

GOVERNANCE SYSTEM

Government Political System in Bhutan. The Local Government Act of Bhutan was enacted on September 11, 2009, by parliament of Bhutan in order to further implement its program of decentralization and devolution of power and authority. It is the most recent reform of the law on Bhutan’s administrative divisions: Dzongkhags, Dungkhags, Gewogs, Chiwogs, and Thromdes (municipalities). The Local Government Act of Bhutan has been slightly amended in 2014.

The Local Government Act of 2009 establishes local governments in each of the twenty Dzongkhags, each overseen ultimately by the Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs. The Act tasks all local governments with a variety of objectives, including promoting Gross National Happiness, providing democratic and accountable government, preserving culture and tradition, promoting development, protecting public health and discharging any other duties specifically created by other law.

District Government – The Kingdom of Bhutan is divided into 20 districts (Dzongkhags). Dzongkhags are the primary subdivisions of Bhutan. Each dzongkhag has its own elected government with non-legislative executive powers, called a dzongkhag tshogdu (district council). The dzongkhag tshogdu is assisted by the dzongkhag administration headed by a dzongdag (royal appointees who are the chief executive officer of each dzongkhag). Each dzongkhag also has a dzongkhag court presided over by a dzongkhag drangpon (judge), who is appointed by the Chief Justice of Bhutan on the advice of Royal Judicial Service Council. The dzongkhags, and their residents, are represented in the Parliament of Bhutan, a bicameral legislature consisting of the National Council and the National Assembly. Each dzongkhag has one National Council representative.

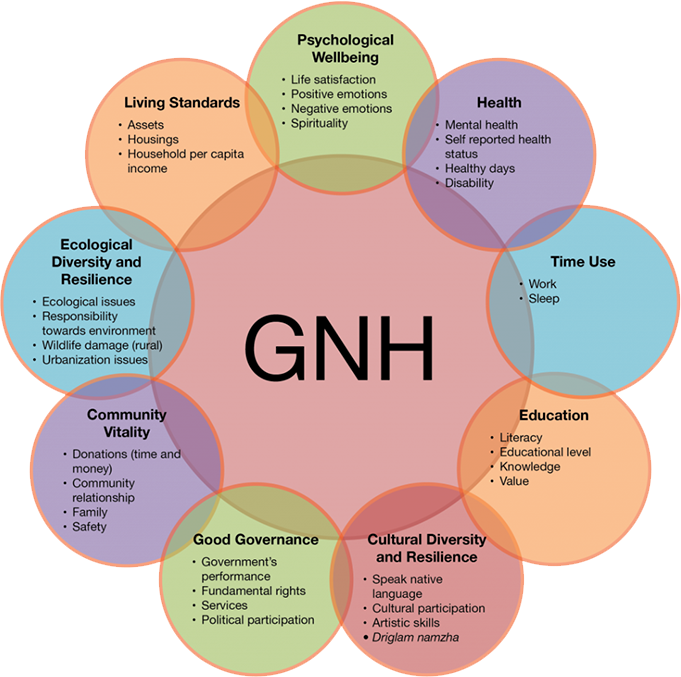

GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS (GNH) MODEL

The phrase ‘gross national happiness’ was first coined by the 4th King of Bhutan, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, in the late 1970s when He stated, “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product.” The concept implies that sustainable development should take a holistic approach towards notions of progress and give equal importance to non-economic aspects of wellbeing and happiness.

Since then, the idea of Gross National Happiness (GNH) has influenced Bhutan’s development policy, and also captured the imagination of others far beyond its borders. In creating the Gross National Happiness Index, Bhutan sought to create a measurement tool that would be useful for policymaking and create policy incentives for the government, NGOs and businesses of Bhutan to increase societal wellbeing and happiness.

The GNH Index includes both traditional areas of socio-economic concern such as living standards, health and education and less traditional aspects of culture, community vitality and psychological wellbeing. It is a holistic reflection of the general wellbeing of the Bhutanese population rather than a subjective psychological ranking of ‘happiness’ alone.

GEOGRAPHY & ENVIRONMENT

Bhutan’s geography is defined by the rugged terrain of the Himalayas, which creates three main regions: the northern high Himalayas, the central inner Himalayas, and the southern subtropical foothills. The country’s environment is characterized by significant biodiversity, dense forests that must be maintained at over 60% of the total land area, and a carbon-negative status largely due to its extensive forests and hydropower. Its climate varies from subtropical in the south to alpine in the north, with monsoons affecting western and central parts of the country.

GEOGRAPHY

LOCATION:

A landlocked country in the eastern Himalayas, bordered by China to the north and India to the south.

LANDFORMS:

The landscape is dominated by mountains, with elevations ranging from subtropical plains in the south to snow-capped peaks in the north.

HIGHEST POINT:

Gangkhar Puensum is the highest peak and is the highest unclimbed mountain in the world.

RIVERS:

Major rivers like the Amo Chhu, Wang Chhu, and Drangme Chhu flow through the country, forming fertile valleys and providing hydroelectric power.

CULTIVABLE LAND:

Due to the steep terrain, only a small portion of the land is arable, with agriculture constrained by the rugged landscape.

ENVIRONMENT

FOREST COVER:

A constitutional mandate requires Bhutan to maintain at least 60% forest cover at all times, and currently, the land is over 72% forested.

BIODIVERSITY:

Bhutan is considered a global biodiversity hotspot with rich flora and fauna, including endangered species like snow leopards and Royal Bengal Tigers.

CLIMATE:

The climate varies significantly with altitude:

South: Subtropical and humid

Central: Temperate, with warm summers and cool winters

North: Alpine and cold, with permanent snow on the highest peaks

CARBON STATUS:

Bhutan is a carbon-negative country, meaning it absorbs more carbon dioxide than it emits, primarily due to its extensive forest cover.

PEOPLE &

CULTURE

PEOPLE

The Bhutanese people evoke a strong sense of individuality and independence. They can be largely categorized into three main ethnic groups- the Tshanglas, Ngalops and the Lhotshampas.

The Tshanglas are commonly known as Sharchops and are considered the aboriginal inhabitants of eastern Bhutan. It is said that they are the descendants of Lord Brahma. The Ngalops speak Ngalopkha and are of Tibet origin. They are known for dances that are unique to them. Lastly, the Lhotshampas are found in the southern foothills of the country and they practice Hinduism.

Hospitality is an in-built social value that they hold high in regards to Bhutan. Their chooce of clothes are distinct too. Bhutanese men are dressed in knee-length robes with belts and women wear simple colourful blouses along with a brightly coloured jacket.

CULTURE

The Bhutanese people evoke a strong sense of individuality and independence. They can be largely categorized into three main ethnic groups- the Tshanglas, Ngalops and the Lhotshampas.

The Tshanglas are commonly known as Sharchops and are considered the aboriginal inhabitants of eastern Bhutan. It is said that they are the descendants of Lord Brahma. The Ngalops speak Ngalopkha and are of Tibet origin. They are known for dances that are unique to them. Lastly, the Lhotshampas are found in the southern foothills of the country and they practice Hinduism.

Videos